Table of Contents

ToggleCross Ventilation in Everyday Buildings

Open a window on one side of a room and another on the opposite side, and you feel the difference immediately. Air starts to move, temperature feels lower, and the space seems fresher.

That simple effect is cross ventilation. It uses natural pressure differences around a building to drive air through interior zones without relying only on fans or compressors.

For designers and facility teams, cross ventilation becomes one tool in a broader AIRFLOW CONTROL strategy, not a complete replacement for mechanical HVAC.

Wind, Pressure, and Airflow Paths

How wind creates pressure zones

When wind hits a building facade, it raises pressure on the windward side and lowers pressure on leeward surfaces. If you connect those two sides with openings and interior paths, air tends to flow from high pressure to low pressure.

The strength and direction of this flow depend on:

- Wind speed and prevailing wind direction

- Building orientation and neighboring structures

- Size and position of openings on each facade

Cross ventilation works best when designers think about these factors at the master-planning stage, not just at interior fit-out.

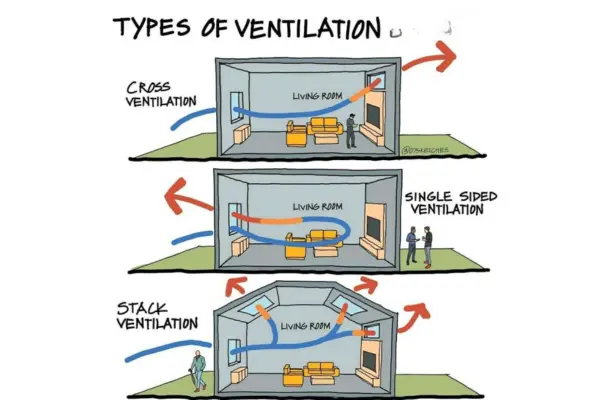

Cross ventilation versus single-sided ventilation

Single-sided ventilation uses openings on one face of a room. Air movement relies on local turbulence and small pressure shifts around that single facade.

Cross ventilation connects at least two external faces of the building or two different pressure zones. Air can enter on one side, move through the space, and exit on another side. This pattern usually delivers deeper and more reliable airflow than single-sided schemes, especially in deeper rooms.

Using Cross Ventilation in Architectural Design

Orientation, openings, and facade strategy

Design teams often start with climate and site data. They study prevailing winds and solar exposure, then position key rooms so they can open toward favorable wind directions.

Common tactics include:

- Placing operable windows or vents on opposite or adjacent facades

- Combining low-level inlets with higher-level outlets to encourage flow

- Using balconies, fins, or shading to protect openings from rain and excessive sun while still admitting air

The goal is to let wind pressure do useful work without creating uncontrolled drafts or comfort complaints.

Interior layout and air paths

Cross ventilation depends on interior connectivity, not just outer walls. If doors stay closed or partitions block flow, the effect collapses.

Design details that help include:

- Internal openings or transfer grilles above doors

- Corridors that align with expected airflow paths

- Limited use of deep, closed-off interior rooms in naturally ventilated zones

In mixed-mode buildings, designers may reserve naturally ventilated layouts for perimeter zones and use full mechanical conditioning deeper inside.

Limits and Risks of Relying on Cross Ventilation

Climate, comfort, and predictability

Cross ventilation responds to weather. On still days, or when wind changes direction, airflow can drop below what the space requires. In very hot or humid climates, moving outdoor air may not deliver acceptable comfort for all occupants.

Designers should treat natural cross ventilation as:

- A primary strategy in mild climates with favorable winds

- A seasonal or partial strategy where temperature and humidity swing widely

- A comfort enhancer that reduces mechanical load rather than a universal solution

Energy models and comfort simulations help quantify when cross ventilation can meet targets and when mechanical backup is necessary.

Noise, pollution, and security

Openings that admit air also admit sound, dust, insects, and sometimes polluted outdoor air. They can also affect security and privacy.

To manage these risks, projects may use:

- Louvered or baffled openings that limit views and direct sound

- Filters or insect screens that sit behind grilles

- Restricted-opening hardware for windows in higher-risk locations

- Operational rules that limit natural ventilation near busy roads during peak pollution periods

Cross ventilation must integrate with the building’s safety, security, and indoor air quality strategy, not compete with it.

Combining Cross Ventilation with Mechanical Systems

Mixed-mode operation

Many contemporary buildings use mixed-mode ventilation. They allow natural cross ventilation when conditions are favorable and switch to mechanical ventilation or cooling when they are not.

Controls and operations teams can:

- Use sensors for temperature, humidity, and outdoor air quality

- Define setpoints for when to close windows and enable mechanical systems

- Coordinate natural ventilation with exhaust fans in restrooms or service spaces

This approach keeps comfort and code-required ventilation more stable while still capturing energy savings when natural wind conditions help.

Role of mechanical exhaust and supply

Even in cross-ventilated zones, mechanical fans often support:

- Local exhaust from bathrooms, kitchens, or high-moisture areas

- Minimum outdoor air rates during low-wind periods

- Smoke control or emergency pressurization in stairwells and escape routes

Natural cross ventilation improves day-to-day comfort and reduces load, but mechanical systems still carry core FIRE SAFETY and compliance responsibilities.

FAQ

What is the difference between cross ventilation and single ventilation?

Cross ventilation uses openings on at least two sides or pressure zones so air can enter, pass through the space, and exit elsewhere. Single-sided ventilation relies on openings on one facade only, which limits airflow depth and often makes performance more sensitive to small wind changes. Cross ventilation usually delivers stronger, more consistent air movement.

What are the rules for cross ventilation?

Effective cross ventilation needs pressure difference, connected openings, and clear air paths. Designers orient openings toward likely wind directions, provide inlets and outlets of similar capacity, and avoid interior blockages. They also consider noise, rain, and security, then pair natural ventilation with mechanical backup if the climate or building use requires stricter control.

What does cross air mean?

“Cross air” usually refers to air that flows from one side of a space to the other, driven by pressure differences across the building envelope. In design conversations, people use it as shorthand for the movement created by cross ventilation, where wind forces fresh outdoor air through a room and out another opening.

How to cross ventilation?

To create cross ventilation, provide at least two operable openings that connect different exterior faces or pressure zones, then keep interior doors or transfer paths open. Position one opening to the windward side and another to the leeward or side facade. In operation, occupants adjust openings to balance airflow, comfort, noise, and security.

What is the purpose of cross ventilation?

The main purpose of cross ventilation is to improve comfort and indoor air quality by using natural wind pressure to move air through spaces. It helps remove heat, odors, and pollutants, reduces reliance on mechanical cooling during favorable weather, and can support lower energy use when properly integrated into the overall HVAC strategy.

What are the four types of ventilation?

Many guides describe four broad types: natural ventilation driven by wind and stack effect, mechanical exhaust ventilation, mechanical supply or positive-pressure systems, and balanced mechanical ventilation with both supply and exhaust. Cross ventilation belongs to the natural category but often works together with mechanical systems in mixed-mode buildings.

How to check cross ventilation?

You can check cross ventilation by reviewing drawings and walking the space. Look for operable openings on opposite or adjacent facades, confirm interior air paths, and observe airflow on windy days using lightweight materials or simple instruments. In detailed studies, engineers measure air change rates and pressure differences to confirm that design goals are met.

Can cross ventilation help prevent mold?

Cross ventilation can help control moisture by removing humid indoor air and drying surfaces, especially in mild and temperate climates. Lower humidity and better air movement reduce the conditions that favor mold growth. It does not solve all moisture problems by itself, so projects still need proper drainage, insulation, vapor control, and, where necessary, mechanical dehumidification.

About YAOAN VENTILATION

YAOAN VENTILATION delivers optimized air and airflow management solutions backed by nearly three decades of engineering experience. Since 1996, we have focused on industrial-grade ventilation and fire protection systems for commercial buildings, infrastructure, and specialized environments. Our portfolio includes fans, dampers, smoke control components, silencers, and precision aluminum ventilation parts designed to work alongside natural strategies such as cross ventilation. By integrating reliable mechanical systems with thoughtful airflow planning, YAOAN VENTILATION helps projects balance comfort, energy performance, and life safety across a wide range of building types.